04: Loved to Death

The outdoors have an astounding effect on us, but what impact do we have on nature?

Trail Weight is produced and written by Andrew Steven. Our Story Producer is Monte Montepare. Executive produced by Jeff Umbro and The Podglomerate.

Find out more about Eugenie Bostrom and Recreate Responsibility at recreateresponsibly.org

You can read Gabrielle Canon's writing at gabriellecanon.com

Dina Gilio-Whitaker's books "As Long as Grass Grows" and "All the Real Indians Died Off" are available here.

You can see Brooks Wheelan's Instagram at instagram.com/brookswheelan

Dan White's books, "The Cactus Eaters" and "Under the Stars" are available at danwhitebooks.com

The entire episode of KQED's Forum with Marla Stark and Tim Davis can be heard here.

Transcript

Note: Transcripts have been generated with automated software and may contain errors.

Brooks: I don't have any, um-- I don’t have any itch to do it, you know? Like, my friend, Johnny Pemberton really wants to hike Mount Whitney. And I just, I don't want to look down on Bakersfield. Not talking shit to anybody who hikes Mount Whitney, but I was like, why wouldn't we just hike-- Why don't we go to the Cathedral Peak? Like, it's less ambitious, but more beautiful, you know? [Fades out]

Andrew: This is comedian Brooks Wheelan. You might know him from his stand-up, his time on Saturday Night Live, or maybe one of his travel shows.

Brooks: [Fades in] And then I have this other show I make with All Things Comedy right now called, “Travels and Such,” which is-- is really low budget. Me and two comics go, uh, within two to three hours around Los Angeles, camping and spend the night. And, um, it edits together for a really funny 20-25 minutes YouTube show.

Andrew: A group of stand-up comedians from Los Angeles might not be the first people you think of when you think of camping. But when Brooks and I first met a few years ago, I was glad to find out we shared a love of visiting national parks and taking photos.

Andrew: You know, I think if anyone follows you on social media, like, they see, you know, alongside your posts about when you're performing, um, or what you've done on late night--

Brooks: Well-- I mean, no, I'm just saying like, my agents wish I listed when I performed more, but I more prefer nature pics.

Andrew: [Laughs]

Brooks: I am like the-- the definition of like a white guy who likes the woods, who read “Into the Wild,” you know? And I over romanticize things and I go on these grand gestures that are really empty and, and-- deep down. Uh, and I don't mean for them to be empty. But just trying too hard to do something cool I feel like is like-- is the archetype for the type of white dude that I am. [Fades out]

Andrew: I don’t know if this entirely falls under that, but Brooks also made a little bit of news the summer of 2020 when he decided to run two marathons on a bet.

Brooks: [Fades in] And also, like, I kind of learned from doing these stupid marathons during this, that I'm like-- This isn't enjoyable. This is just to like, check something off. Like, why don't I just like run a half marathon and like, do that fast and enjoy it. I don't have any like-- Like the Appalachian trail-- I don't need to-- I don't need to do that. But would I like to do, like, the most beautiful, small part of it? Yeah. Like, would I like to do what you did?

Andrew: Yeah.

Brooks: Absolutely. Sounds great.

Andrew: Brooks isn’t alone. He and I are both part of the growing number of people who are visiting these national parks and public lands. Before I read the studies, I knew this to be true. I’ve been to parks in recent years that close off sections for visitors because parking lots were full. And in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw record numbers of visitors to national and state parks, as people who were stuck inside understood the benefits that nature provides. Every year we see more and more first-time campers.

For someone like me who loves visiting places, I’m excited for people to experience them for the first time. Still, the increase in visitors raises overuse and overcrowding questions and asks, “are we doing more harm than good?” Which leads to conversations about gatekeeping, accessibility, and so much more.

And while most of these questions and statistics focus on the smaller, more “developed” areas of these parks—the so-called 10% or less “paved” sections—more people are heading into the backcountry for the first time as well.

Brooks: I mean-- I really, uh, want to do more backpacking and less car camping.

Andrew: Yeah, no, it's-- this was my first backpacking trip and it was definitely a--

Brooks: I mean, that's ambitious if your first one was three weeks.

Andrew: I mean, It's a weird thing too, because it's one of the most popular trails for, like, long-distance thru-hiking. But it also is still-- Like, you could go a whole day and maybe see one or two other people, But I felt like it was close and there's enough other people out there that if something crazy bad happens—

Brooks: Yeah you’re not gonna “Into the Wild” yourself

Andrew: No. [Fades out]

[Theme Music]

Andrew: I’m Andrew Steven, and this is “Trail Weight,” a podcast about hiking outdoors and the lessons learned along the way.

[Clip - “Skyline hike over the Muir Trail” ] The Sierra Nevada range and encloses California famed central Valley on the east. The Muir Trail follows its crest from Yosemite park to the top of Mount Whitney.

Andrew: Unlike Brooks, I had the itch. Even now, a year or so after we rerouted our thru-hike and skipped it, I’m planning trips in my head to get back to the Sierra to reach its summit. But like Brooks, the beauty of nature and the attempt to experience and photograph it greatly inspires me.

[Clip] It is difficult to capture the charm of this high country with a camera. Like symphonic music—which one must experience many times the gain of true appreciation of all its subtleties—so one becomes more and more sensitive to the infinite and ever-changing duties of a high country. The whole area, to a height of 14,000 feet or more, is covered with flowers growing and rocky crevices.

There were masses of yellow Sierra Primroses along the trail and yellow Columbine, which provided a pleasant contrast to the lichen speckled granite.

Andrew: It’s the beauty of these natural places that is part of the reason we’ve tried to preserve and protect them. And to be fair, our efforts have often been misguided, poorly executed, and at times detrimental, despite good intentions (and sometimes the intentions aren’t even quote-unquote “good”).

Andrew: [Fades in] Another similar phrase I've heard some Rangers use is-- in the Park System is “we want to protect the people from the park and the park from the people.”

Gabrielle Canon: Oooh, Yes. [Fades out]

Andrew: This is Gabrielle Canon

Gabrielle Canon: [Fades in] I’m Gabrielle Canon and I’m a journalist and I write for The Guardian.

The nature of Yosemite hangs in the balance as national parks juggle growth, preservation

Gabrielle Canon | USA TODAY

Andrew: And she has written about some of the effects our modern-day activities have had on the natural landscape and national parks.

Andrew: [Fades in] Because a lot of times, like there's the obvious sort of, like-- if people leave trash or are not good stewards of their surroundings, like, that's the obvious stuff. But I think what intrigues me, sort of, in these conversations is a lot of the people who really do love these places who use them-- You know, just your presence, there has an effect on it. And there's a certain amount of, you know-- The world is constantly changing and affecting everything. But overuse is potentially a really big issue for some of these areas.

Gabrielle Canon: Totally, totally. And I think it's something that we're seeing is happening more. And it's one of these sort of horrible paradoxes, right? Where you want people to be really excited about the parks and you want people to want to participate in preserving them and experiencing them and all of these great things. But of course, the more people that want to do that, that ends up having sort of a negative effect if the infrastructure can't, you know, support that.

And so this is something that I've been tracking for quite a while. And, you know, we've seen the $12-billion backlog of deferred maintenance. I think that's a number that has been thrown around a lot. So that's a number from 2018 actually. And then it kind of ties into this bigger issue of, okay, we know that more and more people are coming to the parks and that the park service, or maybe, you know, the-- the DOI-at-large likes to see more people come. Because that means that they'll get more funding. That means that people will be spending more money. But that also comes then with the added negative of if the infrastructure can't support all those people, then the problem gets even worse. And we go on and on and on.

Andrew: In the 1900s, a typical view of conservation advocated for the mixed-use of public lands. Alongside the recreation activities like camping, hiking, and skiing, conservationists also believed that public land should be used for cattle grazing, logging, and things of that nature.

Groups like the Sierra Club formed with the intention to protect nature by popularizing their benefits. However, as the country’s population rose and the outdoor industry boomed, many of these activities overwhelmingly grew in popularity and began to harm the very thing they were tasked with protecting.

Look at our hike, for example. Even though it is remote and the Park Service limits the number of people who can access it on a given day, it still shows many signs of use. I mean, one could view the trail itself as a scar, cutting through nature. And on our hike, we passed a few sections that had to be rerouted to let earlier trampled areas recover and revegetate, not to mention the times we saw litter and used toilet paper. The JMT was full of signs of use.

Tim Davis: Yeah. And you can-- You can trace the use of, of trails in the Sierra of course, back to Native American trails, to cattle and sheepherder trails and, in, uh, in late 19th century, to the Whitney survey coming in in 1864.

Andrew: That’s the voice of Tim Davis, a historian with the National Park Service.

Tim Davis: What the people who created the trail do is, they build on, um, these explorations. They often, uh, in large part follow existing trails, and what they introduce is the idea of a connecting link between Yosemite and the Kings Canyon area and Mount Whitney.

Andrew: According to the National Park Service, demand for permits to hike the John Muir Trail jumped 242 percent from the years 2014 to 2015.

Marla Stark: And once you see the region, you're just stunned by its remoteness and beauty, and you can also see that it is showing a great deal of wear and tear from use. And, uh, the total use that goes on that trail is considerably higher than what you just mentioned. We're estimating it somewhere roughly around a quarter of a million people. Because they come in through all sorts of side trails to get in. There are many loop trails up there [Fades out]

Andrew: That’s the voice of Marla Stark, President of the JMT Foundation. And this is from an interview she and Tim Davis did on Forum from KQED.

Tim Davis: Yeah, I think you can make a case that it's the oldest long-distance trail in America. The people were thinking about it by the 1890s. The Long Trail in Vermont’s Green Mountains was finished in 1930. There's also the Skyline Trail up in Oregon, which, um, initially goes from Mount Hood to Crater Lake. And, of course, the Appalachian Trail isn’t conceived until 1921 and it's finished a lot later.

Andrew: Over time, as the trail received more and more traffic and sections rerouted for conservation, the exact path has slightly changed from year to year to year. And with overuse in mind, how do you balance following the trail’s original route while adjusting for necessary conservation.

Marla Stark: That's a difficult task to undertake. What we're trying to do instead of making it accurate, is really trying to take the existing network of trails that are out there and aligning them in a way that is most authentic to its original route and the way it was described in many of the very early guidebooks and journal entries that we located in the-- in the archives in a number of different libraries. Bancroft Library, the Sierra Club libraries, the California State archives in order to-- to find the most authentic route. So our team of trails-people took a look at that, and we have, in fact, realigned that, and we're presenting it for review to the various, uh, groups to take a look and see what they think. It does start in Yosemite Valley. It goes up to Tuolumne Meadows and makes a beautiful traverse across the meadow by Parsons Memorial Lodge and Lambert Dome, and then heads South.

[Clip] We walked through all kinds of growth, through forests of pine and fir, and through beautiful mountain meadows where the fresh high mountain air was exhilarating.

Marla Stark: It’s hard to describe-- When I went out there with my friends it was an extraordinary vista. The elevation is hard to grasp. Uh, people may know about the tour of Montblanc in the Alps, you think that is a high elevation trail. Their highest point on that tour is 9,000 vertical feet. The John Muir Trail passes exceed 10,000 vertical feet right away. And right in the center, you have five consecutive passes that are at 12,000 vertical feet or higher. And it really presses your lungs. You are on the top of the California snowpack. This is such a dense snowpack that it serves water to 30 million people in California. I think we all kind of take it for granted because it's right there, but right in the middle of our state is an extraordinary high elevation terrain that is really recognized worldwide as tremendously scenic.

[Clip] An area particularly favored by campers is that around Ray Lake and Fin Dome.

Toward evening time, when the sun faded from view and the ever-changing soft evening lights cast their spell, we forgot the trials and tribulations of everyday life and were at peace with the world, and our sleep was untroubled.

Marla Stark: I think because it has this tradition that resonates with both the young and the old, it's become something that people really want to do, uh, kind of on your bucket list to get done. And it is, uh, seeing what is essentially a tidal wave of public access that is washing over the national parks that it goes through. Uh-- I think Yosemite National Park this year is expecting in excess of four-million visitors, and those people are spilling out into the backcountry in ways that I don't think we’re ever really anticipated. And it's pressing each one of the four land agencies there to come up with regional strategies to try to address this.

[Clip] Goodbye. [Fades out]

[BREAK]

Andrew: Ok, so, back on the trail, we had some, well, I’m not sure quite how to say this, but...

Rocky: [Fades in] Today I'm going to try and poop, and I haven't done it yet.

Andrew: Oh yeah, I pooped in the woods. It's not, not that bad. I really honestly wasn't that gross. Even the part carrying out the toilet paper. Not that bad.

Rocky: Just don't think about it.

Andrew: And just use less toilet paper than you would.

Rocky: Yeah. [Fades out]

Andrew: I promise, I swear, I’m not just bringing up poop again for no reason. There is a purpose to it, but it starts back months before we began hiking, at the very moment I had found out I didn’t receive a backcountry permit. (All of us in the future know we eventually got one, but at the time, it was potentially a significant setback).

Dan White: Um, you were talking about, you were just denied a permit to--

Andrew: Yeah, I just got the notification. [Fades out]

Andrew: This is Dan White, he’s an author and hiker, and we just happened to be talking when I got a pretty devastating email, letting me know I did not have a backcountry permit, something you are legally required to have to hike the JMT.

Dan White: I’m pretty sure we must've gotten some sort of wilderness permit when I was a kid going out there. But it's not like today where everything is online and automated, and it's such a-- sort of a racket with so many people going for it out there. [Fades out]

Andrew: To limit the number of people in the backcountry, agencies often require a permit to protect some of these sensitive environments from overuse. Since the number of people who want to hike the JMT in a given season is more than they allow, you have to apply to a lottery for your permit. Our first attempt—and the first hiking window we wanted—was turned down.

Dan had experienced something similar a few years prior when he was writing a story about Mount Whitney.

Dan White: And I can understand the reasoning behind it, but it just seems so weird. Especially for me when I was out there trying to hike Mount Whitney, and I wanted to hike it so I could clean up after other people. To do like-- To do a story about “Leave No Trace.” And to have it be such rigmarole for the-- for the honor of doing this disgusting chapter.

Andrew: In his book “Under The Stars,” Dan White’s exploration of Leave No Trace—the outdoor principle of limiting your impact on the environment, packing out your trash and waste, and general respect and conservation of the outdoors—led him on a quest to attempt to clean up Mount Whitney.

Dan White: It's funny how even with permitting-- On the one hand, it seems like it's so hard to get a permit-- And you go out there, and it's the whole scene. The outpost camp where I was-- it was crowded. It was so full of people, almost like a little city.

Andrew: Mount Whitney is the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States and the Sierra Nevadas. Because of its high elevation and its sensitive environment, the Mount Whitney Zone has special protections, including permits, quotas, and the use of WAG bags, which brings us back to poop. Most of the time, good Leave No Trace practices include digging a hole for human waste and packing out your trash and toilet paper, but in certain sensitive areas, you need to pack out all of it, which means—and there’s no great way to say this—pooping in a bag. You’re supposed to carry that bag out of the backcountry to throw away when you get down, but unfortunately, not everyone does this. And so, Dan set out with a homemade PVC backpack to take as many WAG bags off the mountain as he could.

Dan White: Its, well-- First of all, it was so gross to see all the WAG bags everywhere. But when things have reached the point where you need to get a permit or your-- there’s a lottery to do it-- when you get this level of this crush of people who want to get away from it all, and they're all there because you're there, it's a whole other set of crazy issues. [Fades out]

Andrew: There are two things I should mention about this. First, at this elevation, there’s not a lot of dirt as we might think of it on top of Mount Whitney. It’s more like gravel but chunkier, so digging a cat hole isn’t as much an option as you’d think. Second, technically you are supposed to carry your WAG bags with you. But on Whitney, unfortunately, not everyone follows this rule. And so you can be standing on one of the country’s most incredible vistas standing beside a poorly hidden, attempted burial of a pile of poop bags. Obviously, this isn’t great.

Dan White: [Fades In] People love and stuff to death, right? [Fades out]

Andrew: Dan’s conversation with me wasn’t the first time I had heard about this worry of loving something to death. It's a question people in the outdoor space have been wrestling with for a while.

Andrew: [Fades in] Just sort of putting this phrase to you, when you hear “loved to death,” what does that-- what does that make you think of, or-- or have you heard that phrase before? How do you see that being used sort of in the outdoor, environmental space?

Gabrielle Canon: Oh my gosh. Yes.

Andrew: Here’s Gabrielle Canon again.

Gabrielle Canon: [Fades in] That phrase really resonates for me, especially because I think, you know, people really do love these spaces and I think each person who's kind of out there, you'd like to think that they-- that they aren't going out with any bad intention, right? Everyone's going out to experience something beautiful and experience something awe inspiring. And then at the end of the day, they leave behind devastation. And whether that's on a tiny scale with their, you know, collective footprints, or if it's something like trash or graffiti or, you know, something that like leaves more of an intentional mark. And that, of course, as we've seen, has had these really, just devastating effects on the places that we love, the places that we are supposed to be protecting. So yeah, I think-- I think that phrase really kind of hits it home.

And as a reporter, I think I've kind of struggled-- This is definitely one of those things that I've had to really check my bias, right? Like I’ve had to, like, look myself in the mirror and be like, okay, I can not write about this from the perspective that nobody but me should be allowed to go to these parks.

Andrew: Exactly.

Gabrielle Canon: Which is how, you know, it's hard to not feel that way sometimes.

Andrew: Well yeah, I mean, that's a-- That's a big critique of like, John Muir who is, you know, especially recently-- a lot of people have had plenty to critique-- but you know, it's like: I want to save this for me and no one else, let's not even put roads in here. And then you get into a question of privilege and access and all that stuff too. So...

Gabrielle Canon: That's exactly it though, right? It's like-- I was someone who was very much a backcountry person, and I really love to have this experience on my own and with no cell service and where you just kind of get to be one with nature. But in order to have that experience, it means that the access has to be really limited. Not only from a sense of-- of how many people we can not allow in via permits or entry or whatever it is. But I think also even when you look at, you know, who gets to be on these lands and people who can't go backpacking have mobility issues or people who prefer to experience nature from the window of a tour bus. [Laughs]

Andrew: Yeah, well-- And there's a cost for backcountry to like, uh-- to have time to take time off, to buy gear that you can, you know, carry out there too. And not everyone has that ability as well.

Gabrielle Canon: When you think about this next generation, like trying to promote this love of the parks in order to preserve it. And so you have these kids who live in cities who may have never even imagined going to a place like Yosemite. So how do we, at the same time as trying to get those kids out in that park for that amazing, surreal experience, how do we also then say, okay, we've got to limit the exposure. And it becomes this, like, really extra complicated problem because the more access you have, the worse that experience is, and the less likely that person is going to feel connected to nature and ultimately say, oh, this is something that needs to be protected, right? It's like, if you're going to sit in a four hour traffic nightmare, just to get into Yosemite valley to have your, like overpriced lunch, it's not an experience that you go home feeling that magic necessarily.

Yosemite Traffic.

Andrew: [Fades in] I'd love to know if you have any thoughts on-- I think I heard you talk about, like, sustainability, and how sometimes that gets intertwined in the story of Indigenous Peoples. And it's, it's like, uh, you know-- People have lived on these lands for centuries and that is the definition of sustainability.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker: Yeah. Well, it comes down to the way Native, you know-- it's a worldview, it's a philosophical framework that, um, Native people have learned over thousands of years of occupying particular ecosystems about what it means to-- to live within the limits of those ecosystems.

Andrew: This is Professor Dina Gilio-Whitaker.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker: Dina Gilio-Whittaker. [Fades out]

Andrew: She is a writer, scholar of Indigenous studies, and a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes. We talk a lot more in an upcoming episode, but for here…

Dina Gilio-Whitaker: [Fades in] There are examples in history where Native societies-- where they weren't sustainable. Where their societies seem to have collapsed. This is, you know, before the arrival of Europeans. The ancient Cahokia people, for example, in the Mississippi river valley, the so-called Mound Builders who peaked around the 1200s and then they decline and then like they just kind of go away or they-- they morph into something else. Which is what the Southwestern tribes today call them like the Cherokee, think of the Mound Builders as their ancestors. But, you know, there's-- Nobody really knows, but there's-- there's a lot of speculation and it's still a major archeological kind of project to, you know-- that they're studying. And so the same is true for the Hohokam people in the Southwest that had these very large, very complex societies, but then they collapsed and the same was true for the Anasazi.

And so why do they collapse? You know, we don't know, but there is speculation-- possibly evidence that the combination of drought and maybe the overuse of resources led to the inability to sustain themselves in these environments and in time. And so-- so Native people are not always the perfect environmentalist. They had to learn through mistakes sometimes about how to respect those environments. And it's, again, it's through this-- this relational worldview by understanding that you are part-- Humans are part of these-- these systems. And when you are in relation to other beings, to other people, to other life forms, there is automatically, you know, an ethic of reciprocity and respect and responsibility. Like that's just what it means to be in relationship. So when you live within that kind of worldview, then you-- you are going to use land in a different way. And that's really-- that's really what it comes down to.

For example, if you look at, um, fire, the-- the practice of cultural burning that was used-- especially here in California, um, fire was not something Native people feared. It was something that they use. And the Karuk people and other people will say, fire is medicine. It's medicine for the land. Um-- The land needs fire. And so, that's why they'll-- you know, they, you know, the-- some of the old log books of some of the early SPansih explorers and other people, you know, talked about, there were fire-- there was always fire burning on the land. Um-- And they just chalked it up to Native people, being, you know, doing it-- being ignorant savages, you know, doing these crazy things. Part of colonization is to shut down those burning practices. Well, now here we are a century later with these out of control forest and massive mega wildfire events. Climate change is only part of the problem. It's because of over a century of mismanaged forests. You know, there's finally recognition in the science world and the conservation world that Native people kind of knew what they were doing. And so maybe they, you know-- we need to listen to the Indians again and figure out new ways of-- or perhaps old ways of, being on the land intelligently. And look, Native people have the knowledge about how to manage lands best.

[BREAK]

Andrew: Um-- so I think first-- this is maybe a little bit maybe formal. Could you introduce yourself and provide a title if you have one?

Eugenie Bostrom: Yeah, um-- I'm Eugenie Bostrom. I am the campaign and coalition coordinator—I guess we'll call it—for the Recreate Responsibly coalition. I said, “I guess,” because, you know, we're still in formation. We're, you know, this coalition that came together over early COVID, um, kind of, lockdown days and have been building ever since then and figuring out kind of our stride and our actual structure. And so I came on early and for lack of a better or official term, we-- we call me the, um, coalition and campaign coordinator or manager, I think on the websites as manager. [Fades out]

Andrew: Before Recreate Responsibly, Eugenie had been working in the outdoors for a long time.

Eugenie Bostrom: I'm kind of, of the mind that like, everything has led me to this point in life. Um, and so-- But I think there are kind of relevant experiences that I have that kind of, like, made it obvious for my friends who had started the coalition to call on me, to ask me to step into this role. And so I will go back a little bit. My first job really was building trails and Yellowstone National Park. I was 16 years old and I went out to Yellowstone for this kind of youth program. And so, you know, I fell in love. I was a city kid from LA and Chicago. Prior to them I literally had never met anyone who had hiked prior to the summarize turned 16. And, you know, it's hard, it's hard not to fall in love with Yellowstone. I did that for a couple of years, the youth conservation Corps. And then I went back and I started working for the National Park Service running some of those programs— some of those youth programs and doing trail maintenance and things like that. And so running trail programs, youth programs at Yellowstone then actually led me to going to work for the National Park Service headquarters, and then the Department of Interior under the Obama administration. And that was a wild ride and amazing. And it was so great to be able to juxtapose my experience in the field with kind of how policy affects those programs and all of that. [Fades out]

Andrew: And so, during the COVID19 Pandemic, when states and cities were closing down certain activities, many new people found themselves visiting parks, campgrounds, and beaches, spending significant time in outdoor spaces for the first time. Many saw the effects these large groups and people had on their environment. Particular seasoned outdoor enthusiasts complained that the “new people” were ruining it for the rest of us, while others pointed out the outdoors should be for everyone, and this trend is ultimately good thing.

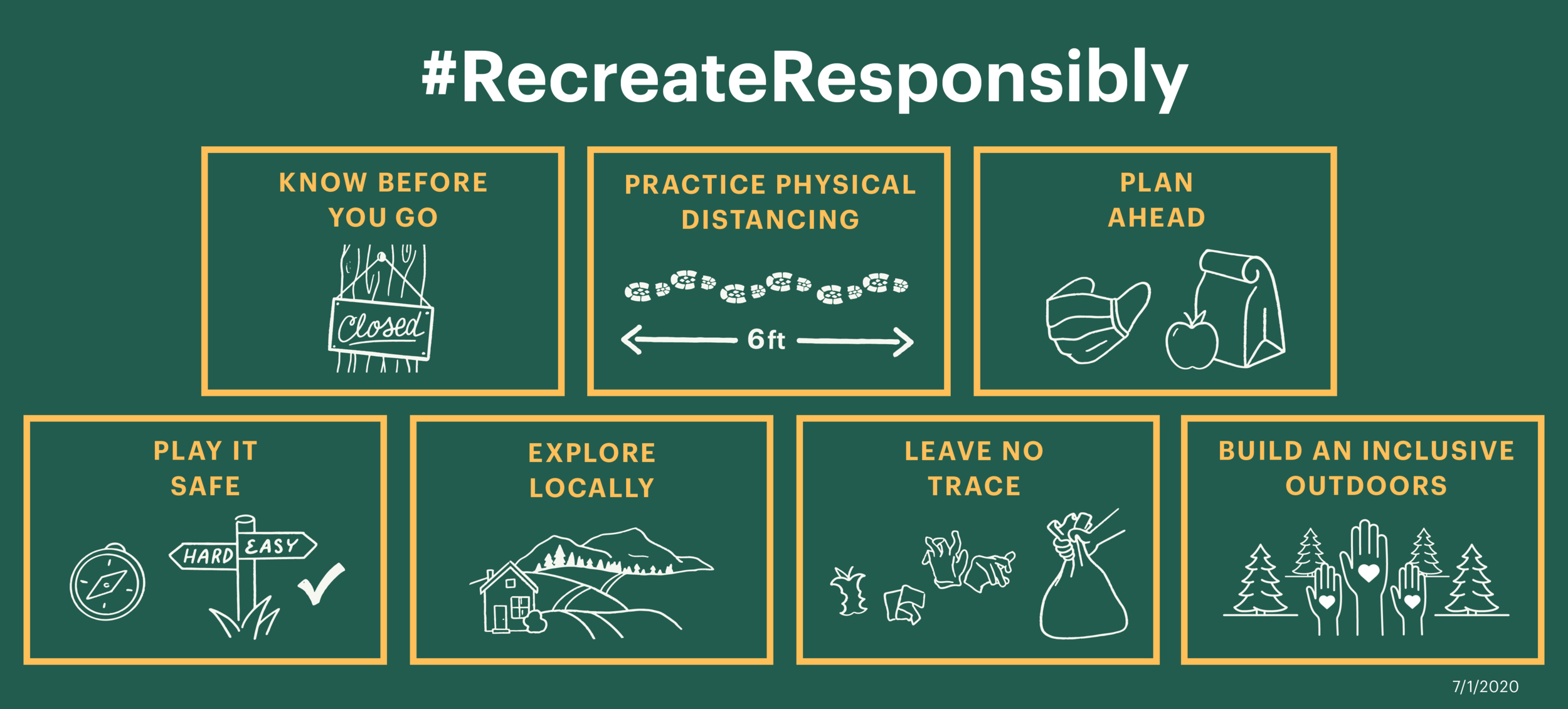

Recreate Responsibly was born from this debate—as a coalition of organizations, individuals, and companies, tasked with creating and promoting guidelines to do just what their name implies: recreating responsibly.

Eugenie Bostrom: The general principle is, in essence, it's think about things before you go, be open to change upon arriving, and then, you know, little tidbits to consider. [Fades out]

Andrew: Guideline number one, “Know Before You Go.”

Eugenie Bostrom: [Fades in] In essence, like, checking the status of the place that you want to go. Uh, it may be crowded. There may be facilities closed. Things like that.

Andrew: Next, “Plan Ahead.”

Eugenie Bostrom: [Fades in] Bringing food, snacks, face coverings stil,l understanding that a lot of places maybe requiring face covering still things like that.

Andrew: Maybe not so obvious, the next one hits close to home.

Eugenie Bostrom: Consider Exploring locally is a critical one. And I think its important so that we don't love it to death or smother. Certainly people think of when they're like, I'm an outdoorist now, they're like, I'm going to go hike Yosemite or Yellowstone or Grand Canyon, But, oh my gosh, do you not get the exact same thing when you're in Griffith park? I know I do. Right? And Griffith park is literally 10 minutes from my house. I mean, people are always surprised to learn how many national parks there are because they only think of the top 10, top 20 top 50 even. Right? But there are hundreds if what we want is to feel that feeling of connectedness and groundedness, and we can achieve that a lot closer without, you know, using as much gas and without potentially, like, getting into the crowds or putting ourselves at risk.

Additionally, the Recreate Responsibly principles are, you know, again came out during COVID. So practicing physical distancing was a key one, and that

Andrew: ...and has implications beyond COVID.

Eugenie Bostrom: Physical distancing will still be crucial, not just for potential COVID safety, but also for being considerate of the fragile landscape.

Andrew: The next guideline is “Play it Safe.”

Eugenie Bostrom: Just reminding people that oftentimes we get really excited. My dog, for example-- my puppy will run himself ragged. Like run circles, and then can't walk for a day. He's an older dog. And so, we as humans often tend to do that when we get excited, it's a new place, we've got endorphins. And so really starting to know your limits. And-- but not only because obviously you don't want to get hurt. But especially right now with increased visitation, uh, Search and Rescue and all kinds of facilities are strained. And so if you get hurt, not only are you putting kind of other search and rescue folks at risk, but you're also like— might not get to you as fast. So definitely something to consider.

Andrew: And borrowing from a more well-known principle...

Eugenie Bostrom: One of the most important ones, something that you're probably really familiar with is “Leave No Trace.” It's interesting to see you Leave No Trace as one of our tips when Leave No Trace itself is an organization and a set of principles. And we did that on purpose because we do think Leave No Trace is important, but we understand that that might be a few layers down for someone who's never experienced outdoors before. We want to use, kind of, our megaphone and our platform to say, “Hey, we're going to introduce you to the concept of Leave No Trace, and we're not going to slam you with all of it right now, but here's-- here's the concept.” And then we hope that that encourages people, hooks people to dive deeper and start learning Leave No Trace ethics as their relationship with the land starts to unfold.

Andrew: And finally...

Eugenie Bostrom: And then of course the foundational one, the most important one that underlies all of this, and that's building an inclusive outdoors.

Andrew: These guidelines and groups and organizations are just the start of a much bigger conversation we need to have about the outdoors and how we use it and how we protect it. And hopefully as we continue to grow and learn and remember we progress.

For many, what draws us to the outdoors is the perceived lack of "rules." But the reality is that every one of our actions has a specific consequence. Being responsible sometimes means doing what you don't want to do. I'm still wrestling with my own desire to go and see and experience without wanting to ask how I'm impacting the outdoors. It's a privilege I have that I’ve taken advantage of for far too long.

I’m that type of person that believes asking questions is sometimes more important than finding answers, but knowing the truth is also very important. As I grow and change, one this I know is, something is calling us to the outside world. It's essential to step out beyond our bubble and experience what the world outside has to offer, and recognize what part we're playing and what we need to change for the better.

[BREAK]

Andrew: Ok, so a slight digression here. When I talked with Dan White, he shared something that stuck with me—probably because it had to do with the metaphor of storytelling and creativity and how it applied to nature and hiking and the outdoors—which is kind of my thing. But whenever I listen back, I’m struck by how applicable it is to many different areas of life.

Dan White: There's something about that “putting a one foot in front of the other and just kind of going for it” that applies to a lot of other stuff. When you do approach a hike like this, you don't know what the outcome is going to be. You don't know where it's going to take you because what this is-- is disruption in a good way.

I just have to say that for me, doing something that throws a little chaos in my life is really important for me. When I grew-- was growing up, I was always on the meek side of things, always kind of risk-averse. That was super bookish, a bit of a self-imposed shut-in, from that perspective. I was not terribly athletic, and I always had this idea of, of sort of weakness, right. But I also felt like I often was really indecisive. I would also-- I would often just sort of wing it.

And when I heard about the trail, actually from a friend of mine, it was something where the open-endedness of it appealed to me because it just looked beautiful and wild and crazy. And I kind of didn't know what was going to happen.

And I think this is really especially true now with search optimization and, and, and websites-- Google and Facebook kind of second-guessing what it is that you need. And you'll find your-- even your reading list will sort of be curated from-- by mysterious forces. Or somehow you'll get these reading recommendations and your feed, and you'll think, oh, these people know me pretty well.

When you go into an experience that exceeds your grasp, that maybe, exceeds, initially your physical capacity to do it, and you start nibbling away at it, and you don't know the outcome, and there's something really scary about it-- But there’s also something really freeing and wonderful about that. And it really does speak to one's career, especially if you're doing a career that involves risk and creativity.

Andrew: This is something Dan knows a lot about. His first book, “The Cactus Eaters,” came to be while thru-hiking The Pacific Crest Trail—a 2,650 mile, five-month journey that stretches from Mexico to Canada (and shares some of the same route as the JMT).

Dan White: I feel like aside from providing me with material to write “The Cactus Eaters,” which, as I've said, was not my intention from the beginning. It's almost as if the trail becomes the metaphor for the writing of it and the publishing of it, to begin with because that is almost as much of a process and a slog as doing a trail. And when I say slog, I meant you need-- if you're doing something that is arduous, you should try to do that joyfully because in a Pacific Crest Trail or in the publishing, you're going to get knocked around. “The Cactus Eaters” — I'm holding the book in front of me now. You see this little, this shiny object in my hand, this physical-- even now, as I'm talking, saying these words, it's sort of shocking and weird. And the reason why it's so weird is because I had a failed “Cactus Eaters.”

Almost immediately after I hiked the PCT, I did think, okay, geez, that is going to be-- that could be a good book. And I set out, and I wrote this book, and I think it was a thousand pages long. And by some weird quirk, I did get a literary agent, and it got shopped around-- and it was rejected by everybody. So “The Cactus Eaters” that exists now-- absolute complete overhaul. It's probably 90% different. And it started because I was sending-- when I was working at the Santa Cruz Sentinel as a daily reporter, my friend, Peggy Townsend, who's a wonderful writer-- I would send her emails because the first version of this book was this big sludgy blah mess. And I would send her emails in which I would try to do scenes and kind of bring it out. And the email format forced me to keep it short and keep it urgent.

And for some reason, I was able to resurrect this just dead blob of a book, and I was able to get it into enough shape so I could apply to Columbia University. And I didn't want to apply to the MFA program ‘cause I thought, for sure, I was going to not get in. My wife, Amy Ettinger, she actually had to pull the application off the ground because I just-- I remember reading it and being so dispirited that I let the application fall on the ground. I don't think I've ever told anybody this.

And she said, “no, you're going to apply.” And I applied, and I got a fellowship. And that's once again, that is not a brag. What I'm trying to say is that you can do more than you think you can with applied effort. You just can. I think it's true for everybody. I do feel like there's something that Thoreau said where if you advance with confidence in the direction of your dreams, you'll have success you couldn't have imagined in your common hours.

I mean, there's something about that “putting a one foot in front of the other and just kind of going for it” that applies to a lot of other stuff.

Andrew: So whether you’re attempting to backpack for the first time, trying to clean up Mount Whitney and the JMT, or making decisions to recreate responsibly, start by taking a single step, and then take another, and one more after that...

This mantra was something I knew from the most challenging moments of my life. It’s what you do the morning after your mom dies and you don’t want to get out of bed. And I was reminded of this quite literally on the trail as we slowly and steadily climbed some of the most challenging sections of the hike.

[Clip] All summer, we've been looking forward to Forrester’s Pass. We gradually climbed the spectacular 13,000-foot pass—the gateway between Kings Canyon and Sequoia park. After taking a final look north, we descended rapidly by amazingly engineered switchbacks blasted out of the sheer granite cliff. We were very glad to be off the top of that pass, which was cold and windy.

Andrew: “Glad” probably isn’t the word I would have used, but we were relieved once we made it over the pass.

Andrew: I’m about a little more than halfway up Forester Pass, and this might be the hardest thing I've ever done. Onward.

[Teaser]

[Credits]