02: Good Grief

What is more difficult, thru-hiking the Sierra or learning how to properly grieve? Andrew and Rocky process these questions as they reflect on Andrew's mom's death and the struggles of hiking.

Trail Weight is produced and written by Andrew Steven. Our Story Producer is Monte Montepare. Executive produced by Jeff Umbro and The Podglomerate.

You can find Niall Breslin's podcasts and more at niallbreslin.com

Transcript

Note: Transcripts have been generated with automated software and may contain errors.

[Voicemail SFX]

Andrew: I never knew how devastating a voicemail could be.

[Theme music]

Andrew: I’m Andrew Steven, and this is “Trail Weight,” a podcast about hiking outdoors and the lessons learned along the way.

When I started making this podcast, I thought it was going to be a story about weight loss. I thought chronicling a year of my life, ending with a month-long backpacking trip, would make an interesting story. I wasn’t expecting it to start with the death of my mom. I wasn’t prepared to tell this story. Of course I wasn’t—I wasn’t prepared for my mom to die. I didn’t know what it would mean for my family. I didn’t know what it would mean for my relationship with Rocky. I couldn’t begin to understand what and how I was processing all of this. I questioned my hopes and reexamined my goals.

If growth requires change, I was fine stunting my growth. This change was too much, too hard to handle… So I threw myself into planning this thru-hike. It was a comfortable and welcome distraction, spending nights Googling tips and reading blogs from previous hikers. I watched almost every YouTube video of people’s hikes, searching for secret revelations about where to camp, what gear is the lightest, and what to expect.

And just like that, almost one year exactly after my mom’s death, my dad picked up Rocky and me from our place in Los Angeles and drove us the 200 miles to our campground in the Eastern Sierras, where we would start this long hike the next morning.

Andrew: It is Tuesday, July 30th at 6:28 pm, and Rocky and I just finished dinner.

Rocky: And Andrew's dad just headed out.

Andrew: Yeah, my dad dropped us off at Crabtree Meadows Trailhead campground.

Rocky: Yep. [Fades out]

The drive to the Eastern Sierras.

Andrew: The car ride up was a mix of small talk, my dad checking we had everything we needed, and perhaps a little bit of parental jealousy. While we were talking, there was also a hope that specific conversations wouldn’t happen... A little bit of backstory, growing up, I don’t ever remember getting grounded. Instead, we’d always talk it out, debate, and discuss whatever happened. Dinners were always loud, and everyone talked over everyone. But as I grew older, some of my views shifted from my parents (as they do). And as much as our arguments might have been based out of love—trying to convince the other because you want them to see things from a new perspective you thought could help them—I soon learned that very rarely can’t you argue someone into change.

My dad admitady likes to win. In his mind, it’s “Either convince me I’m wrong, or I convince you you’re wrong.” Perhaps as a reaction to this, I became much more of a “You can’t lead someone where they don’t want to go” type of person. This naturally caused some tension. It can be challenging to believe in someone’s intentions while struggling with their conclusions.

The year after my mom’s death understandably brought up many things held loosely under the surface. Working as a podcaster isn’t necessarily the most lucrative career, and my dad worried about my future. He couldn’t understand why I preferred to live in Los Angeles when there were so many beautiful suburbs. And I wasn’t going to church as much as he’d like. But we’d usually find some common ground for conversation.

I hoped our long ride to our campsite wouldn’t bring up painful or well-trodden topics. I wasn’t looking forward to talking about them right before entering the backcountry with no cell service or internet and with plenty of idle time to replay conversations and imagine arguments.

Andrew: You were just saying right before we started recording that you're scared about being bored?

Rocky: Yeah. Not scared, but--

Andrew: Nervous?

Rocky: It’s a weird thing to be scared about. But after a while, you kind of get lost in your thoughts, and sometimes the thoughts are not good. [Laughs]

Andrew: Yeah. Being alone with your thoughts can be a privilege--

Rocky: --bad.

Andrew: but it can also be very, it can be, uh-- you can start to sort of fold in on yourself.

Rocky: Which is easy for me. [Fades out]

Andrew: It’s easy for me as well. And it’s part of the reason I ended up here. And so, in the spirit of over-analyzing, let’s rewind a little bit.

[Nature SFX]

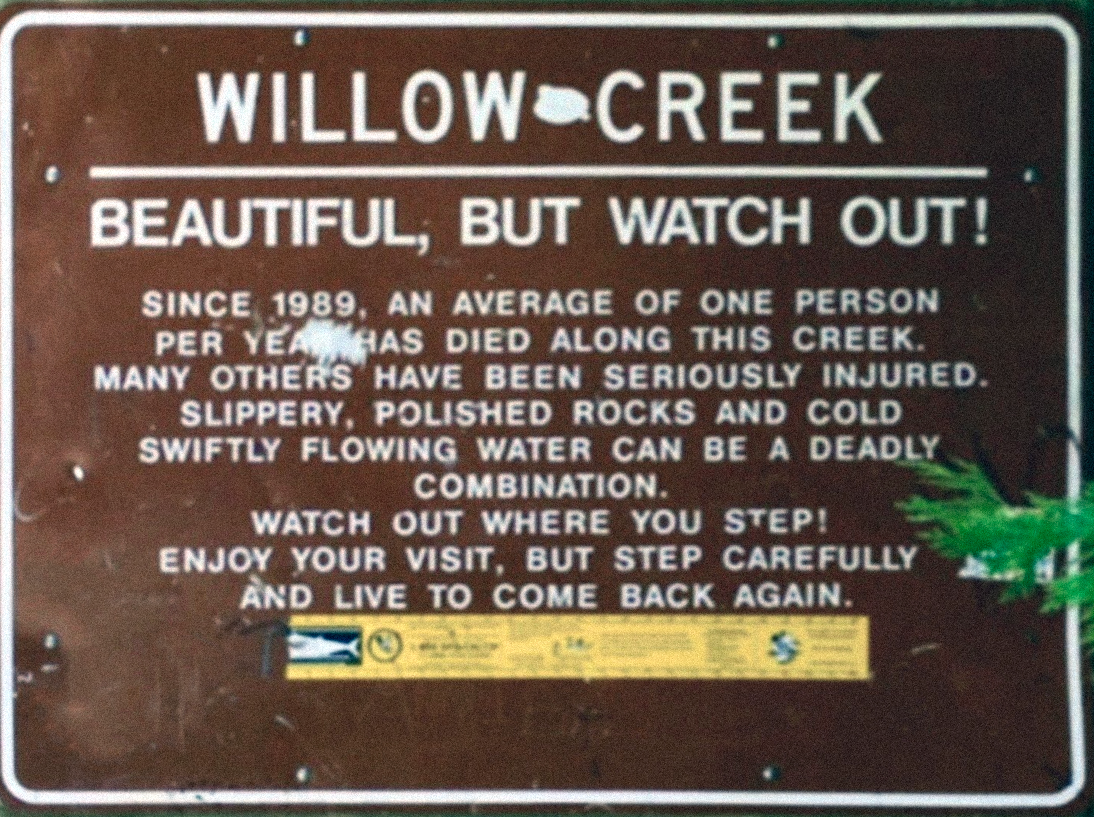

Sign at Willow Creek Trailhead.

Andrew: For most of my childhood, my family would go camping with a group of our friends every Memorial Day weekend. Twelve years in-a-row we camped at Hume Lake, a small mountain lake just outside of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. After that, we switched it up and ended up camping at what would become the new regular, Bass Lake, a small mountain lake just outside of Yosemite National Park. Weirdly, I’ve almost grown up on either end of this trail. Perhaps this subconsciously placed the idea in my mind of hiking for a month through the Sierra Nevadas? The only thing was, back then, I hated hiking. I didn’t mind walking to the camp store to buy candy, though.

Anytime we had planned an afternoon or day hike, I would only begrudgingly go. It didn’t help that one of our family’s go-to hikes was Angel Falls—whose trailhead prominently showcased the exact location where people had died during their treks to the waterfall. I don’t know why they would do that and name the waterfall after a creature from the afterlife. Who was the PR person for this hike? They were giving me every excuse not to have to hike it. Truthfully though, it wasn’t safety concerns that fueled my distaste for hiking. I was fighting against the pain and discomfort of exercise. I was ashamed.

The first time we set off on the trail to Angel Falls as a group, we stopped near a creek for lunch, about halfway up the trail. After a short rest, some of the group decided they wanted to wait while the majority went on to finish the hike. We’d all meet up again on their way back down. I chose to be part of the group that stayed behind. This didn’t make my dad happy. At some point, he decided to turn back from the group hiking and came back to get me. I think he had good intentions, but I really didn’t want to finish the hike. I started walking back up with him, and we argued as we hiked on, trying to catch up with the rest of our friends. Eventually, we turned around and never made it to the falls.

A smaller group of our family and friends would go on to hike this same trail the following year, and the next, and so on. To this day, I’ve never finished it.

Yet, here I found myself, one day into a 200-mile long hike.

Packing up in the morning.

Andrew: July 31st, we made... what's it called?

Rocky: Breakfast?

Andrew: Yes... Oatmeal! We made oatmeal for breakfast.

Rocky: And some chocolaty, chocolaty, chocolaty milk.

Andrew: Some Instant Breakfast-- Carnation Instant Breakfast to get some calories. Um, and it seemed like when we woke up, Rocky, you had sort of done a 180?

Rocky: Yeah, I woke up feeling excited about the-- what we're doing and how pretty it is up here. It's already so crazy. And it's so pretty [Fades out]

Andrew: Forgetting the word “oatmeal” on the first real day of the hike was not the type of hardship I had expected on this journey.

Andrew: We’re doing a couple of shorter days in the beginning so we can sort of get used to the altitude and get our bodies used to walking this many miles with our big heavy packs on them. [Fades out]

Andrew: This was a tip I had read in the months of preparation leading up to the hike. I created a spreadsheet with the number of miles between possible campsites, elevation gains, water sources, and more. Keeping miles short in the beginning was an easy and practical solution that made sense on my computer. But there are greater challenges that don’t fit as nicely into the little boxes on a Google Doc.

[Phone Ring]

Donald Black: Hello.

Andrew: Hey Donald, how’s it going?

Donald Black: Good, man, how are you?

Andrew: Good, can you hear me alright? [Fades out]

Andrew Black: This is my friend Donald Black.

Andrew: So random question, I guess not so random, um, but you’ve hiked, you've done some backpacking... Just randomly, for no apparent reason, uh, what advice would you have to someone who's never backpacked before who's thinking about doing the JMT? That person is me. [Laughs]

Donald Black: [Laughs] Good to know. [Fades out]

Andrew: He was the only person I knew who had done something like this, so I wanted to know ahead of time what I was getting myself into. He told me that, yes, it would be physically challenging, but a long-distance thru-hike can also be challenging to your brain and emotions.

Donald Black: You gotta work on, like where your brain is going to be? Feeling low-- because it’s really hard, it’s like-- How do you train your brain? [Fades out]

Andrew: If you couldn’t work that out, he said, “You have to work on where your brain is going to be” and, “how do you train your brain?” Yes, I could work out for months on end, trying to get my body in the best possible shape, but that was only part of the process.

It was exciting having the goal of completing this backpacking trip, which required me to get to a specific physical level. Having a concrete date and a reason for my fitness goal (and the accountability of making a podcast about it) helped me begin to see real, physical transformation for the first time. But the idea of training my brain seemed more daunting. What does that even mean? We don’t have gyms for our minds, or is that what therapy is? I had been avoiding answering these questions because it would force me to actually deal with my issues, not to mention the compounding fact that when I started training for this hike, my mom had cancer for a second time.

If I’m candid, when my mom got sick, it was motivating in a weird and selfish sort of way. It's cliche, I know, the whole “#YOLO-live-like-you're-dying-bucket-list” sentimentality. But seeing what my mom was going through was a daily reminder of how our futures aren't guaranteed and how it's not worth making excuses and putting things off until tomorrow. And so my training, my journey, my goal had a new and strange motivating force.

Andrew: You know, a month ago in July, I stepped on a scale, and I weighed 396 pounds. That's, that's four pounds away from 400 pounds, which is a lot.

Andrew: When I set out on this journey to hike for a month through the Sierra Nevadas, I thought this would be a story about weight loss. Little did I know it would be about loss of a completely different kind.

Andrew: Two days ago, my mom died. It still feels weird saying it out loud.

In May/June-- in the end of May-- beginning of June, um, we found out she had abdominal cancer. Um, and just a year before that she had colon cancer. And so we were all very worried. She was in a lot of pain and um… [Fades out]

Andrew: Every week, I’d drive the hour drive from Los Angeles to Orange County to visit my Mom. My mom was weak and didn’t have the energy for long conversations. But I wanted to be there regardless. Most weekends, I went home to be there for my mom and ended up being there for my dad.

Andrew: And, uh, the doctors basically gave us a diagnosis that without chemo or without treatment, it would be a few months And, uh, if the treatment worked well, it could be a year to maybe three years at best. And um… [Fades out]

Andrew: Three years was a timeframe I could wrap my head around. Enough time to properly say goodbye, share moments and memories. But that wasn’t the plan. Soon I’d learn what “palliative” care meant, as I watched my mom and dad choose between prioritizing her comfort or attempting new treatment that would increase her pain in hopes it could heal her.

Andrew: And then on Wednesday night-- late Wednesday night, early Thursday morning, she woke up and, um, she was taken to the hospital, and uh, passed away there at the hospital.

And uh, I woke up Thursday morning to a message from my dad.

I don't know why I am recording this, but...

Andrew: I must have slept through the ringing; I called my dad back, and we cried. I waited in an unnatural shock for Rocky to get home from work. Before I could tell her, she saw it on my face. She cried “No!” in disbelief. This was all happening too soon. How can something be both expected and unexpected at the same time?

I was sad and angry, and all the things you feel when a parent dies. I had firsthand evidence of the whole future-is-not-guaranteed thing. My mom wanted to go to the beach one more time, go camping with her friends one more time, sleep in her own bed instead of the rented hospital one in the dining room one more time. But there wouldn't be any more times.

[BREAK]

Andrew: Almost one year after my mom’s death, Rocky and I were going over our packs and waiting for my dad to pick us up.

Andrew: It is July 30th. The morning we leave. Where are you doing?

Rocky: I’m getting sandals.

Andrew: How are you feeling about your trip?

Rocky: I’m feeling good, tired, nervous, happy, excited, sad... I don't know? It's a mixed bag of emotions.

Andrew: Would you say you're more excited or more nervous?

Rocky: Um, I actually-- I think I'm more nervous, even though it doesn't come across that way, ‘cus I'm realizing how I express nerves is by shutting into myself. Like where I'm like, “everything is fine,” everything is-- Like, I feel like I don't feel any emotion right now.

Andrew: You're numb.

Rocky: I’m numb. Cope, baby, cope.

Andrew: Yeah. I'm-- I think, uh-- I just got nervous cause I think my pack's heavier than I was expecting.

Rocky: Oh, I don't even want to know...

Andrew: ‘Cus I kept on adding-- like, I did-- I forgot to, to consider the weight of the recording gear and...

Rocky: It's very heavy?

Andrew: No, but just a bunch of little stuff add up, you know?

Rocky: Yeah.

Andrew: So it'll be fine, but it's just-- it's, it was-- it was a lot lighter a week ago. [Laughs] [Fades out]

Andrew: In preparation for the hike, I researched and weighed all the gear we planned to take, entering it into a spreadsheet so we’d know what to expect when we first felt the total weight of our packs. I thought if I could see it on my computer screen, it would somehow prepare me for the experience of it. Yes, visualizing is important, but it was also my way of trying to control the unknown.

While I made these lists, it reminded me of the half-hearted debates I used to have with my mom. She was an over-preparer. I am an over-planner. Looking back, they were both attempts at avoiding stress and pain, but I was convinced my way was better. This was such a part of our relationship that it even made its way into her eulogy.

Andrew: My mom was always over-prepared. And that's to say, in my opinion. Whenever she was sick or someone was in the hospital, she'd learned the lengthy, complicated term for whatever ailment and recited it in perfect Latin. She carried around seemingly hundreds of reusable shopping bags in the back of her car. So many that it seems like it would fill an entire shopping cart. Leaving one to wonder if when she shopped, she would take two carts, one full of bags and one for the groceries. I have two in my car. [Fades out]

Andrew: I used to think my mom’s desire to have “extra” was her way of not planing or not thinking ahead. It bugged me because I felt that if she just planned a little more, her life would be better, and it would cut down on what I thought was an unnecessary abundance or even waste. In a way, now I can see this was her planning. The piles of shopping bags in her car were just a different way of grasping for control. My way of controlling an unknown situation was to be minimal, systematic, and efficient.

Andrew: My mom and my dad and I-- we all like to go camping, and I'm the type of person who thinks I already have way too much camping gear, and I romanticize, like, people can just take everything in a backpack, and that's it. But my mom brings not one but two coffee makers in their huge trailer. And one day, we were talking—I was teasing her about how much extra stuff she brings—and we went through the trailer, and there was a bag of dog food. And to put this in context, my parents didn't even have a dog at the time. And this was proof. Who goes camping with a few gallons of dog food when they don't even have a dog? Mom said that she had it in case one of her camping friends needed it for their dog if they ran out of food. She really loved being able to help someone out like that.

Looking around, not just in her trailer, but everywhere in her life, you could see how mom was orchestrating everything so that she could help someone if they needed it. Her heart was big, with room for others, and she would always put her comfort aside if it meant she could help someone. I think that's proof to why we're all here today. We've all experienced a little bit of mom's kindness and love, her friendship, and tireless support, and dog food, literal or metaphorical. I love you, mom, and I miss you. [Fades out]

Andrew: We’re all always trying to be in control.

When my mom was sick, one of my brothers spent nights researching how certain foods might extend my mom’s life or help fight the cancer. My other brother took the opportunity to spend even more time with his family and teach his kids about grief and loss.

I tried to quantify it.

When my mom died, I tried to figure out the most efficient way to grieve.

Niall: You know, you need to be allowed grief. Grief, If you repress it, it does really difficult things. And what happens with grief is it comes out somewhere. If you try to repress it, it is going to come out. And I always say it to somebody, and I've lost-- I've had friends who've lost loved ones, and they always say to them let come out on your terms. Let it come out in your-- I will never be uncomfortable with your pain. If you ring me in the middle of the night and you're sobbing, I will never be uncomfortable with that. I will never ask you to internalize that.

Andrew: This is Niall Breslin.

Andrew: How, how do you, uh, like-- is there a way that you like to be introduced? Are you a podcaster/author/musician?

Niall: Honestly, whatever you feel. I'm not touchy about it. Um, but yeah, no, I, I-- I do lots of different things, but I'm not very protective of any of them.

Andrew: While he does do a lot of really fantastic things, I first got to know Niall because of his work with and his study of mindfulness.

Niall: I'm a mindfulness therapist; I did my masters in mindfulness-based interventions-- I've always found this area really interesting.

Andrew: The story I’m kind of telling is a-- it’s a period of my life where nothing went as planned, so to speak. And I decided to go on a month-long backpacking trip. [Fades out]

Andrew: I recounted the story of my training, my goal, and my mom’s death to Niall to get his take on it.

Niall: You experienced acute grief, which is the most painful pain on earth. And the problem with that type of pain is, often, as individuals, we're forced to repress it or internalize it or to pretend it's okay. But really, if we all express grief the way we felt it, we would just scream and scream and scream and fall apart and cry. But we're not allowed to do that by society.

And one of the most common phrases you'll hear in Ireland is “I'm grand.” No, you're not. You're in the worst pain you've ever experienced. And really, this is where it comes down to it for me, Andrew, is--

Our culture and our society forces us to internalize what is very normal human feelings and emotions. And the people around us who are really uncomfortable with those difficult emotions force us to internalize them.

Andrew: I’ve heard it said that internalizing these emotions can be like pressing on the gas and brakes of your car at the same time. When we try and ignore or press down these feelings, we create stress. Ironically it's a fear of stress that motivates me to internalize and silence the overwhelming emotions. (This doesn’t work with the analogy, but I feel the need to point out my mom drove with both feet, right on the gas, left on the brake. Apparently, this is how Formula-1 drivers drive, but I don’t think she learned it from them. It was just how she’d always done it, but she made sure to teach me not to do it).

As I dealt with my mom’s death, I thought grieving efficiently meant I was grieving well, but in reality, my efficiency was a way to get it over with as quickly as possible. I wanted to move on. I didn’t want to feel this pain anymore. Practically, I still had a date circled on a calendar, I had a backpack I still needed to buy, and many more miles I needed to walk if I was going to be able to do this hike. And all of that was a welcome distraction that helped me avoid the depression that comes after losing a parent.

Andrew: I felt a very strong pressure to be like, you know-- Oh my mom's in a better place-- this is a good thing. I mean, it's sad that we're going to miss her obviously, but it's like, I understand and I can, I can-- I don't, I don't fault anyone for saying those or coping that way, but it-- it also felt strange sometimes. Like denying what was actually going on.

Niall: There is an element of comfort to that. You know, if you believe that, and there is-- and we shouldn't take that away. But at the end of the day, that shouldn't stop you being in all sorts of pain, because pain is good. I know this sounds [like a] ridiculous thing to say, but pain means you're alive.

Andrew: This is never more evident than when you’re hiking at elevation with a twenty-something pound bag on your back. Without a doubt, this thru-hike would be the most physically challenging thing I’d ever do. From day one, I lost count of how many breaks I need to take to catch my breath. Rocky would often hike ahead and wait for me at the top of a climb, and I worried she was annoyed at my slow pace. My feet hurt. My back hurt. My knees hurt. Even if I wasn’t tired, I’d stop at every rock or stump that was chair-height, so I could sit down without the extra effort of having to take my pack off and putting it on again.

Even though I felt the pain of thru-hiking, my body felt better and stronger than it had since I could remember.. Every time I rested, I was filled with a sense of awe and wonder and surrounded by beauty. And every sore spot, achy joint, and labored breath was a constant reminder that I was here, on the trail, this day, and it wasn’t a date on a calendar anymore.

Niall: So mindfulness is a buzzword that has been really commodified and transformed and redefined to be digestible to the Western world, essentially.

Andrew: Okay.

Niall: For me, mindfulness is that window into your soul. And it is the ability to sit with the good, the bad, and the ugly. Everyone thinks mindfulness-- and this is the perception we've created is, ‘cus every image you see is just this girl or guy looking perfectly happy, sitting on a rock with the sunset behind them. Most of my meditations are horrible, and I'm bringing up stuff I don't want to be bringing up. But I can bring it up, and I can sit with it because I've trained myself to sit with that stuff. And that's the stuff that does the damage. That's the stuff that can really hold you back and let you suffer and, and fill you with shame and guilt. And if you can disempower that stuff, if you can break that down and, and say, listen, I've experienced this, but you are not defining me anymore. That's the real power of mindfulness. And I'm not saying that is-- in terms of mindfulness-based therapy, that's essentially what you're doing. You're trying to get people to sit with the things they don't want to sit with.

Andrew: This is unavoidable when you’re hiking for hours a day, alone in the mountains. The thoughts will find you. I doubted my ability. I felt I was holding Rocky up. And I just spent a day in the car with my dad on the anniversary of my mom’s death. Was this hike a retreat, or was I retreating? By not taking the time to sit with the things I didn’t want to sit with, it was like I was hiking without a map. If you’re not constantly checking in with your surroundings, it’s easy to get lost.

Niall: The first thing I-- I would say is feel it all. Like genuinely feel at all. Every emotion is valid. Bring a real deep curiosity to every single emotion you experience. Curiosity is a really powerful thing. And it's one of the principles and practice of mindfulness based interventions. So when you feel that slight overwhelm when you sit down after a long day, and you sit down, you get a bit upset ‘cus you, you bring up a memory of your mother... Sit with us and be curious to where in your body you are feeling it. Do I feel it in my chest? is this? ‘Cus it will manifest itself physically in your body, every single time, your body and your mind literally are allies, they high-five each other, they are completely aligned. So as soon as you feel that emotional charge, you're guaranteed that you'll feel it somewhere in your body and put your hand in and go, oh my God, that’s kind of interesting, I feel it there.

Andrew: At home, in the city, with work, it’s easy to justify pushing off dealing with the “things” later. I’ll wait till it’s the “right” time to analyze my emotional wellbeing. Not to mix metaphors, but on the trail, there’s only so much you can do to keep these thoughts at bay. Eventually, they come flooding in like a tidal wave. I built up distractions as a makeshift seawall in my “everyday life,” but here I found myself swept out to sea wearing floaties and a backpack.

Niall: Explore this stuff. Really explore this stuff. This is, this is the stuff. This is the stuff that will make you. It really will make you. This-- you know, getting up and going to work and getting promoted or doing what, that's not going to make you. Trust me. What's going to make you, what I always say, sometimes we can see far better than the dark and things become clearer to us in the dark.

And that's kind of a weird thing to say, and we often hear “the dark night of the soul,” you've often heard that phrase, but you've had yours. You know, you've had yours, and you've come through it, and you've found a way to deal with it. What I would say, be bloody proud, be proud of your humanity, to be able to do that, to experience the pain, to have the self-awareness to go I need to get out of here for a while, and I need to disconnect. That is not you running away. Actually, that's a very difficult thing to do. Running away would be training five times a day, would be drinking yourself, so you don't have to deal with the actual physical pain. The most difficult thing to do would be to pull yourself away from the world and be with your own thoughts. That’s powerful stuff. And something you should be very proud of because not many human beings would have the courage to do that. So that's what I would say.

Andrew: Well, there's the other stuff too [Laughs]. It's a mix of both.

Niall: But like, but the reality is it's still, yeah, we can, we can beat ourselves over the head about the other stuff that's inevitably going to happen. Or we can look at the stuff that you managed. But you know, we've all experienced grief, and it's torturous, and it's-- it's easy to avoid. And that's what our-- that's what our culture is-- has basically built upon in terms of our emotional wellbeing, avoidance, avoidance, avoid this difficult stuff.

Andrew: I’m still wrestling with this process. It seems like some days are solidly in the ‘avoiding’ column, and others definitely fall under ‘feeling.’ Most of the time, I’m probably somewhere in the middle, feeling just enough to make it seem like I’m doing the work but not going as deep as I could. But then again, as Niall might say, there’s some comfort in that. I just can’t let it stop me from feeling anything at all.

[BREAK]

[Water SFX]

Niall: I don’t want to be hyperbolic here, but nature was definitely something that potentially saved my life. Where I live in Westmeath, the Mullingar Garden in the center of Ireland we’re surrounded by lakes. Beautiful, beautiful glacial lakes. And at my-- I suppose at the-- at the height of my kind of fight-- I don't even like calling it a fight. It was just at the height of my journey with it. I made this call to get into the lake Lough Owel every morning, just to-- and again, Irish lakes are all year round Baltic. They are freezing.

Andrew: [Laughs]

Niall: And if you want to learn what mindfulness is, get into cold water. That is the single best way to make yourself feel alive, to feel mindful, to be present, to understand that you control your breath, that you can control and deal with your panic. Because that's, what happens when you get into cold water, your body goes into hyper fight or flight. You start panicking, and you go, “no, I’m going to control my breath.” It starts to become really empowering. And the lake became part of me and so much so that I have a tattoo of me holding the lake in my hands, because I think that lake has something special in it.

[Water SFX]

Andrew: What are you going to do?

Rocky: I’m thinking about jumping into this, this here pond. Just run…

Andrew: You’re not gonna do it?

Rocky: No, I am. It’s just cold. It’s hard. [Laughs]

Andrew: Three, two, one…

[Water SFX]

Andrew: How was it?

Rocky: I don’t know, I’ve never done cocaine, but I bet that’s what it feels like. [Laughs] [Fades out]

Chicken Spring Lake.

Niall: I go into a different world in nature. It just does something very-- I live in one of the most beautiful countries in the world to be outdoors. And even though it rains and it's cold, that rain and that cold is what will make you feel more alive. There's nothing like a Northwest wind North Atlantic west wind cutting the arse off you to make you feel mindful and present. And I've been in California as well. I know California also has one of the-- some of the most beautiful places I've ever seen in my life.

Yeah-- and I think with nature, you don't need to experience-- we don't need to see you experiencing nature, experience it yourself. I don't need to see you taking pictures of it. It’s grand. You have your moment. You live that moment.

Andrew: You just undermined it this whole podcast because it's a-- [Laughs] it's essentially a retelling of my experience at nature. So...

Niall: Oh no, well. [Laughs] [Fades out]

Rocky in the tent.

Andrew: We are now inside of our tent, in our sleeping bags, at 6:30 [pm]. Ready for bed. [Laughs]

Rocky: Well, gonna eventually make a trek out to go find a poop spot.

Andrew: Yes, this will be your first time pooping in the woods.

Rocky: Have you-- I've pooped-- In the woods-- What? [Laughs]

Andrew: Wait? What? [Laughs]

Rocky: No, nevermind. I’ve done things, okay.

Andrew: Have you dug in a hole? A cat hole?

Rocky: No, I haven't. I haven't done a cat hole. I take that back. I've pooped in a lake. [Laughs]

Andrew: That's worse. [Laughs]

Rock: I know it was horrible. [Laughs]

Andrew: Why are you admitting to this? [Laughs]

Rocky: I don’t know. [Laughs]

Andrew: This is on record. [Laughs]

Rocky: This is horrible. I'm not going to go into detail because I could. [Laughs]

Andrew: I don't want you to-- it's already too much. [Laughs]

Rocky: Well, you know where to find me if you want the full story [Laughs]. I went swimming in this lake.

Andrew: Oh yeah, that's right. [Laughs] Not the poop lake.

Rocky: [Laughs] Chicken Spring Lake.

Andrew: Yeah. We went to Chicken Spring Lake. We got here in the afternoon, and um, we went-- it was cold. Rocky went all the way under.

Rocky: It was really cold.

Andrew: I just went up to my knees. But, tomorrow to Rock Creek. Um, anything we missed?

Rocky: Oh yeah, but-- so I did a 180 in the morning to be like, excited and looking forward to everything. And now that it's the night time, I am sad again. So hopefully, I'll do another 180 in the morning again [Laughs] and be happy, excited. I think I’m just tired...

Andrew: What is someone, like diagnoses us when listening to this? [Laughs]

Rocky: Hey, I'd take it if it's for free, sure.

Andrew: I'm definitely in the, um, it's becoming more real-- and so the joys that come with that are showing themselves and the pains and struggles.

Rocky: Yeah. Yeah. I was tired, and I miss TV, and a bathtub. [Fades out]

[Teaser]

[Credits]